How primitive were graphics in video games in their early days? Some games didn't even have graphics. Instead, these games had textual descriptions of your environments and the on-screen action. You interacted with these games using a command prompt.

How primitive were graphics in video games in their early days? Some games didn't even have graphics. Instead, these games had textual descriptions of your environments and the on-screen action. You interacted with these games using a command prompt.

One of the first computer games was Willie Crowther's Colossal Cave Adventure. Crowther developed the game, based on the Mammoth Cave system in Kentucky, on the ARPANet mainframe on which he worked as a defense contractor. He actually developed it as a way to connect with his daughters following their parents' divorce. You explored the cave using a two-word parser. Your object was to find treasure and safely escape the cave. If you fell into a trap, you lost one of three lives, which would be accompanied by a humorous message. This set the template for many games to come.

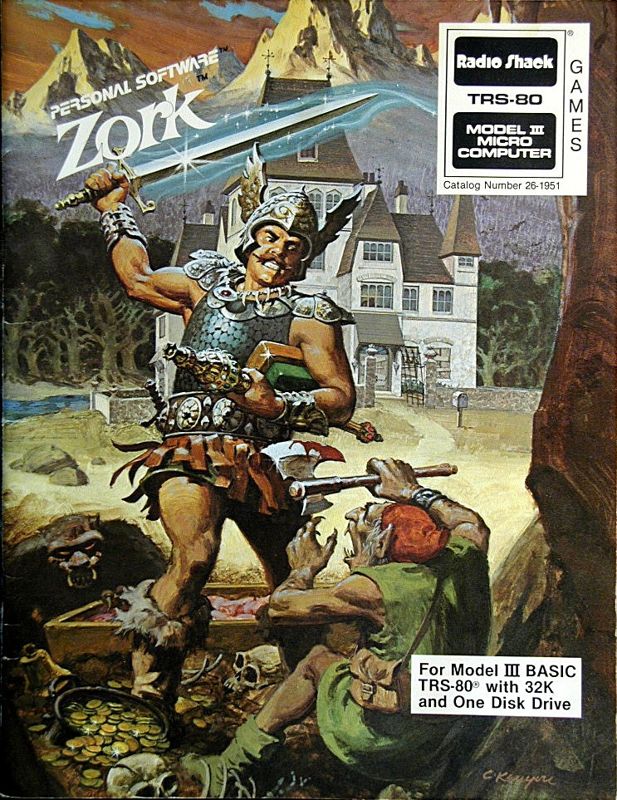

In 1977, MIT students Marc Blank and Dave Lebling created their own version of Colossal Cave Adventure, naming it Zork. In 1979, they knew they had a hit on their hands, and founded a company called Infocom in Cambridge, MA, with a number of friends and business associates ("implementors"). Over the next few years, they would release 36 or so text adventures, which Infocom branded as "Interactive Fiction."

In a typical Infocom game, you would be placed in a game world, ranging from fantasy, to sci-fi, to mystery, and other genres. The game presented you with text-based descriptions of your surroundings, items that could possibly be interacted with, and descriptions of directions you could travel. As you traveled, you had to read the descriptions carefully so that you would know where to go, and just as importantly, what dangers were lurking about. These dangers could come in the form of monsters or environmental hazards. Depending on the game, the monsters could be battled in turn-based combat, though without visible hit point counters and with the chance that the RNG could deal the player a one-hit death, or a certain object or spell was needed to defeat them. Environmental hazards ranged from subtle, to falls into pits or cave-ins. For instance, if the game indicated that you smelled gas nearby, it most likely wasn't a good idea to bring an open flame source into the area. Failing to heed these dangers would lead to a humorous description of your character's death.

Infocom's games were considerably more sophisticated than text adventures from competitors like Scott Adams's Adventure International. Infocom's games generally allowed complete sentences rather than simple two-word verb-object parsers. Of note is the fact that MIT, where Zork was originally developed, was also where a famous early computer program called ELIZA was developed in 1969. ELIZA, one of the earliest known "chatbots," was notable for being able to simulate a degree of conversation with a human user by matching word patterns entered by the user, and it is likely that Infocom's parser was built on its designers' experiences with ELIZA.

In addition to the games themselves, Infocom games usually included a bunch of physical goodies in the box, as a number of computer games back then did, similar to the Collectors' Editions of today's games. They could be toys, comic books, and other literature. These were known as "feelies" and often helped develop the backstories. In many cases, the "feelies" also served as a form of copy protection. Cutthroats, for instance, required coordinates out of a book of shipwrecks that was included in the game box, as the needed information was nowhere to be found in the game itself.

Notable Infocom games:

- The Zork series, created by Lebling and Blank, was Infocom's "killer app," and was arguably one of the best-known game franchises of the early 1980s. A fantasy adventure with a number of comedic twists, Zork is set in the ruins of the Great Underground Empire, which collapsed under the rule of Lord Dimwit Flathead and the Frobozz Corporation. You arrive at a nondescript rural house in the country, equipped only with a sword of Elvish workmanship and a battery-powered brass lantern, in order to protect yourself from being eaten by a lurking grue, and must explore the GUE across three main chapters (the three chapters were actually a single game on a MIT mainframe, but had to be cut into three parts for the home computer market.) A prequel game written by Steve Meretzky detailed the last days of the GUE. Zork was one of the early phenomena of computer gaming, with a number of games and even a few Choose Your Own Adventure-style books as tie-ins Zork games continued to be produced until 1997, by which time the series had adapted a first-person graphical interface similar to Myst.

- The Enchanter series (Enchanter, Sorceror, Spellbreaker) is directly related to the Zork series. You play as an novice magician who is sent to defeat the evil warlock, Krill. The highlight of this series is its magic system, where you are given a magic book that has several spells with silly names (such as "frotz," which turns objects into light sources) and varying effects. More spells can be written into your spellbook using another spell. Usually, you must "memorize" a spell before you can cast it.

- A trio of murder mysteries (Witness, Deadline, and Suspect). Of these I had the third and hardest game, Suspect, set in the wealthy Washington, DC metro, where not only did you have to solve the mystery, the murder of a wealthy heiress at a costume ball, but you had to clear your own name, as you were the prime suspect at the beginning due to the murderer leaving evidence pointing to you.

- Cutthroats, an adventure where you played as a diver hired to salvage a sunken ship for treasure. This adventure required the "feelies" included to help you determine which wreck to salvage, so I didn't figure this one out until Internet cheats were available. In addition, you had to avoid having your dive sabotaged by a rival salvaging company.

- Suspended, an adventure where you interacted entirely with the game's world through a group of robots, each of which has different senses and abilities. In this game, you are in charge of operating the systems which keep natural and artificial disasters at bay on your planet, all of which are malfunctioning, so you'll need to send the right robot to do the right job. All the while, hell continues to break lose. This game was considered to be the most difficult Infocom game of all time, and with all the calculations the game had to do at any one time, it tended to make computers run slow. The feelies served as copy protection in that the robots provided rather limited descriptions of the environment in-game, particularly in regards to directions. You were expected to use the included map and tokens to mark the location of each robot as you moved them through the facility. Side note: the "implementor" who wrote this game, Michael Berlyn, would go on to create Bubsy the bobcat as an attempt to build an animal mascot media franchise during the 16-bit console generation.

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy was the single most successful game in Infocom's history. Douglas Adams, the author of the Hitchhiker Trilogy (which by then included four books), worked closely with Steve Meretzky on the game, which was based on the first half of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. You (mostly) play as Arthur Dent, following his adventures trying to save his house from being bulldozed to make way for a bypass by Mr. Prosser, only to have to escape with his friend Ford Prefect just as Earth itself is demolished by the Vogons to make way for a hyperspace bypass. One of the most infamous puzzles is the Babel Fish vending machine puzzle, which you can lose permanently (but not know it until much later) by failing to pick up an item early on in the game. The game does have sections where you play as other characters such as Ford, Zaphod, and Trillian in events that occurred before the plot of the book. There were plans to develop a sequel based on The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, but Infocom's financial struggles and lack of resources killed the project. The rights to the game eventually reverted to Adams's estate. This game is now available online through the BBC's website.

- Plundered Hearts was the only infocom game to be developed by a female "implementor," Amy Briggs, and is styled as a pot-boiler interactive pirate romance novel. As such, it is one of the few Infocom games written from a distinctly female perspective.

- The Leather Goddesses of Phobos is a softcore adults-only title based on 1930s sci-fi serials. Originally a joke at the Infocom offices, Steve Meretzky developed it into a game based on the premise of "The Hitchhiker's Guide, but with sex." Your adventure begins in a depression-era bar in Upper Sandusky, Ohio, where you must find a bathroom quickly before you wet your pants. The game determines your character's gender by which bathroom you choose to use, and the object is to save the Earth from being turned into a big pleasure palace for a group of interstellar dominatrixes. By this time, Infocom had a rivaly going with Ken and Roberta Williams's Sierra On-Line. Sierra's competing game, Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards, makes fun of TLGoP at one point.

Infocom lasted until 1989. They were hugely successful in the early 80s, but as graphical computer adventures and RPGs became available, on home computers and eventually on the NES, Infocom's sales rapidly declined. In 1986, Infocom was bought by Activision, and the relationship between Infocom and its new parent company was constantly rocky. Activision eventually forced Infocom to move development out of Massachusetts to California, and by 1989, Activision, which had brieflty changed its name to Mediagenic and was itself teetering on bankruptcy, shut down Infocom. Activision Blizzard still holds the rights to Infocom's titles, save for The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. Despite the complete lack of graphics, I invested a fair amount of gaming time in my early years playing these games.

How primitive were graphics in video games in their early days? Some games didn't even have graphics. Instead, these games had textual descriptions of your environments and the on-screen action. You interacted with these games using a command prompt.

How primitive were graphics in video games in their early days? Some games didn't even have graphics. Instead, these games had textual descriptions of your environments and the on-screen action. You interacted with these games using a command prompt.

Comments