Dr. Mario is definitely a product of the initial Tetris craze. Similar to titles like Columns, it's pretty slow and basic, but still not bad. My mom loves Dr. Mario, though. It's one of the few video games she'll be willing to still play! Also, Hip Tanaka's music in it is awesome.

Dr. Mario Review Rewind

|

|

See PixlBit's Review Policies

On 05/15/2020 at 09:00 AM by Jamie Alston I hear he’s got the cure. |

Most can enjoy the concept it was going for. However, said enjoyment might be short-lived.

To describe Dr. Mario as a falling block puzzle game would be slightly misleading. In lieu of descending blocks, you’ll have to guide vitamin capsules raining down from that dubiously credentialed pill-popping Mario. I mean c’mon— he’s a plumber practicing medicine in the “Mushroom Kingdom”. It’s a Dateline investigation waiting to happen. Mark my words.

Released on both the NES and Game Boy in 1990, Dr. Mario was one of the many games that capitalized on the popularity of Tetris at the time. Back then, I loved anything Mario-themed, and my older brother had this on the Game Boy given to him as a middle school graduation gift in 1991. Being the generous big brother that he is, he would often let me play his games when he wasn’t using it. So naturally, I played this for as long as I could before having to return it.

All is not well in the Mushroom Kingdom Hospital. While Mario is conducting research in his lab, nurse Toadstool (a.k.a. Peach) informs him that one of his experiments have gone haywire, causing viruses to spread quickly. Fortunately, Mario developed a new medical breakthrough in pill form that should take care of the problem. And that’s where he needs you.

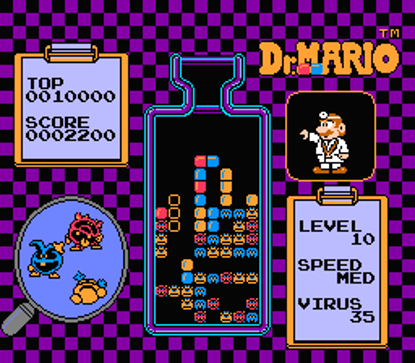

The goal is to clear each stage of all red, blue, and yellow viruses in the bottle by matching them to at least three vitamin capsules of the same color. You can do this either vertically or horizontally. If the bottle gets full beyond the threshold at the top, it’s game over. Sounds easy, right? And for the first few levels, it’s simple enough. But soon after, you’ll notice a few complexities.

While most Tetris clones focused on clearing lines of blocks, Dr. Mario takes a more fragmented approach with an emphasis on navigating around objects and frequent improvisation. The capsules have two halves, often with two different colors. If you match four of the same color of only one side, the remaining portion(s) will break down into smaller caplets that drop down to whatever is beneath it. This presents an interesting challenge because the viruses are often grouped in tight clusters which quickly becomes a problem when destroying adjacent enemies if the capsule above them doesn’t match the color of the virus it touches.

Essentially, you’re not only fighting against the viruses but also constantly having to work around the aftermath of your decisions of how best to position each pill. Placing one on top of a mismatched virus can easily get out of hand if you don’t focus and plan your next move carefully. But thanks to the multitude of viruses in most levels, you’ll have to balance between careful planning, rapid decision-making, and nimble dexterity for good measure. Those combined gameplay elements introduced a layer of strategy that was unseen to this degree in puzzle games at the time.

What intrigues me about Dr. Mario in terms of overall enjoyment is that it appears to have been designed around the Game Boy’s hardware more so than the NES’s. While playing on the NES gives you the obvious benefit of full color and a 2-player mode sans the need for a link cable, that seems to be the only real advantage to playing it on the home console.

On the Game Boy, the controls feel a hare tighter. The music- while still the same tunes as on the NES- in my opinion, sounds a bit cleaner on the Game Boy, especially the “Chill” theme. And when you eliminate two or more viruses at the same time, there’s a brief chime that is strangely missing from the NES version for some reason.

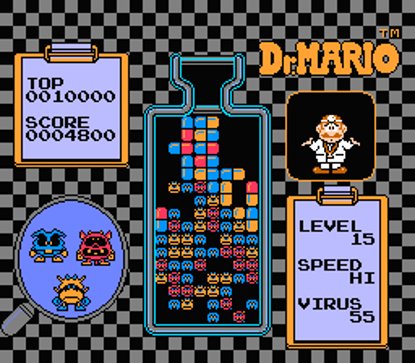

Unfortunately, the simplicity of Dr. Mario is its biggest drawback. Once you get the hang of matching pills to clear out each virus, there’s not much else to do in the game. It’s just level after level of an increasing number of viruses to challenge your ability to problem-solve color combinations. While there is a 2-player vs mode, it’s basically the same thing except you can make random pieces fall on your opponent by clearing a chain of multiple viruses in one move.

That isn’t to say that the game is entirely at fault for its lack of variety. When it was originally released, the bare-bones presentation was generally on par with our expectations for what a puzzle game should be. However, it has been outmoded by later iterations and the advancements in the puzzle genre in general. I sometimes forget just how accustomed I’ve become to doing things like quick-dropping objects or seeing the ghost image of where they will land until I go back and play games like Dr. Mario in its vanilla form. The absence of such features presents a gap that makes the game less of a snappier experience than it was in its heyday.

To be clear, I do consider Dr. Mario to be a fairly enjoyable game. The concept of a medically-themed falling block puzzle combined with Nintendo’s charming character designs gave the game its own personality which further helped to distinguish it as being more than just a cheap Tetris imitator. But in terms of prolonged enjoyment, results may vary depending on how much you like its no-frills repetitive nature.

Personally, I will always remember Dr. Mario for teaching me the importance of medicine. It’s a notion that I’ve carried with me into my adult years. Every time I read a label for antibiotics instructing me to take the full prescription even if I feel better, I always think about those red, blue, and yellow viruses hanging on for dear life until my meds have destroyed each one.

Comments